tirto.id - The epoch of Indonesian Communism did not start with Henk Sneevliet as mainstream Indonesian historiography has told us. It began with Leendert J.D. Reeser, a teacher of history and geography in Hogere Burgerschool (HBS), Surabaya. Dutch author and historian Annie-Romein Verschoor, who went to Surabaya’s HBS as a student in the early 20th century, describes her teacher as a stocky man with chubby cheeks, stout rounded head, and reddish skin he dubbed “as red as himself” (Verschoor, 1971).

Verschoor’s recollection of Reeser provides a vivid portrayal of the man. “Reeser the Red,” writes Verschoor, took the seat, put down his glasses, lit his tobacco pipe and started off his class—much of it revolved around topics on historical events in Europe and the Indies. He posed critical questions addressing the rights of native Indonesians, the position of women in society and what stance a European was supposed to take in regards to colonialism. In her account, Verschoor, a female pupil sitting on the front row, tells the unease she felt of getting struck by Reeser’s bold “question everything”.

Among Reeser’s charming gestures dearly remembered by Verschoor was his habit of standing on his own seat before the classroom while delivering Roman-style oratory speech—a manner said to have inspired Sukarno to practice his speech inside his study at Tjokroaminoto’s house.

Apart from his teaching job, Reeser’s personal idiosyncracy had turned himself into gossip material among his students. The fact that he never minced words about the Dutch royal family was widely talk about among Surabaya’s small European community. Every weekend, Reeser and his wife spent their time in the Marinegebouw (“Marines’ Club”) located in Oedjoeng (now the Port of Tanjung Perak). Sometimes his wife stepped in to dance with sailors—which even more spiced up existing rumors on Reeser.

The Spirit of the Age

Back in the Netherlands, the young and spirited Reeser was an active member of Social Democratische Arbeiders Partij (SDAP) or Social Democratic Labour Party, as he retrospected in an article written in 1899, two years prior to his departure to the colony.

In series of articles narrating the late 19th century Europe, Reeser liked to emphasize what he considered as the zeitgeist (“spirit of the age”) of the fin de siècle, i.e. “the victory of altruism over egoism” brought about by the labour movement sweeping across the Old World. “How pleasant life is,” wrote Reeser quoting a line from a 16th century Dutch humanist and reformer Ulrich von Hütten, “since the zeitgeist has awakened,” (“Overzicht der Wereldgeschiedenis in het jaar 1898”. Vragen van den dag, vol. I, 1899). Such were altruism and spirit of the new age embraced by Reeser upon embarking his professional life in the Dutch Indies.

He started working at the HBS as a school teacherin 1902 and was assigned to permanent teaching post a year later. Alas, the colonial situation was a far-cry from that of Europe imbibed in the zeitgeist as the Colonial Constitution (Regerings Reglement of 1854) prohibited any political activities, including those organized by Europeans.

However, in 1916, the Governor-General Idenburg’s political reform aimed at gradual changes in the colony introduced a major revision to the draconian laws. Yet, the soulless colony had sent Reeseer to the state of despair. In fact, his long-desired “age of altruism” had to deal with harsh egoism of Europeans in the colony: a class of fortune seekers wanting to go home with huge savings before, as the popular saying goes that time, “getting old in the Indies”.

Reeser was no passive observer of history. Despite the prohibition, through a reader’s letter published in SDAP’s paper Het Volk in July 1903, Reeser called for socialist fundraising in the colony as a preparation for Dutch 1905 election.

“With the help of a friend in West Java, I have now been working to establish a fundraising association (Kontributie Vereeniging),” Reeser writes. “It will be mandatory for every member of the association to donate up to f1 each month. Donation will be made anonymous and sent under my name through postal receipt.” (“Een Indisch Verkiezingfonds”, Het Volk, July 19, 1903).

Despite membership being limited to Dutch citizens, Kontributie Vereeniging had in practice become the earliest socialist club in the Indies. Yet, the secretive nature of their activities made them soon forgotten.

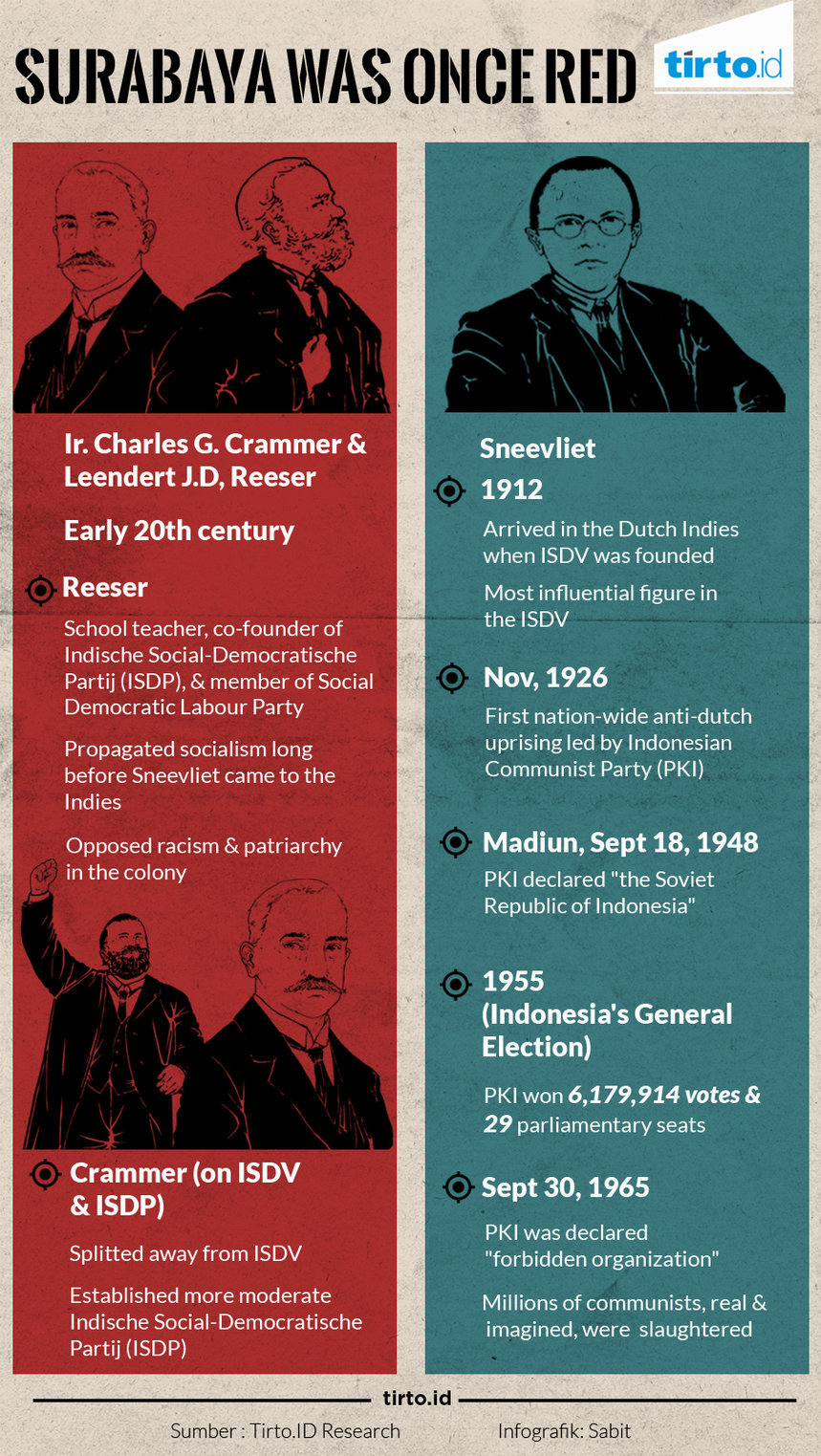

The existence of Kontributie Vereeniging was barely taken into historical account until Charles G. Cramer revealed his role in the fundraising through an interview published in Het Vrije Volk on October 20, 1959. The co-founder of Indische Social-Democratische Partij (ISDP)—later to be elected to Volksraad (Dutch Indies parliament)—spoke of his participation in the association. His membership number was 48.

According to Cramer, there were 68 financial backers identified only through membership number and the sum of each donation—names and postal address were not mentioned. In 1910, Clamer claimed, donation to KV had amounted to f2.672,02 which was transferred immediately to SDAP’s treasury in the Netherlands (“Ch. G. Cramer Tachtig Jaar”. Het Vrije Volk, October 20, 1959).

Like Reeser, Cramer was among early 20th century Dutch Indies socialists. He was born in the small town of Sidoarjo, East Java, into a European family that were long-time colonial residents. Having finished his secondary education, Cramer went to Delft University, a mecca for left-wing students and Marxist-oriented thoughts. Socialist leaders such as H. van Kol (SDAP founder) and many others were trained in this “red college”. After graduation, Cramer returned to the Indies and worked as an irrigation expert at the Office of Irrigation and Public Works (Waterdienst en Burgerlijke Openbare Werken).

Cramer’s testimony led Reeser to write a reply in the Het Vrije Volk's readers section. He explained why the collected fund was transferred in 1910, 5 years late from the original plan. It was difficult to make any transfer to SDAP, Reeser argued, as De Javasche Bank was hesistant to take any risk due to the political nature of the transfer. In fact, in the era where the colony suffered from political isolation, the bank was unwilling to take any action prone to be construed as opposing the government. The leftist club was thus left with no choice but to postpone the transfer and reallocate the fund to another bank.

The Socialist Middenstand

The Marxist axiom of “the base determines the superstructure” figures prominently in Reeser’s life story and politics, something of which perfectly illustrates the early phase of modern socialism in Indies.

After spending 17 years in London, one of the most advanced industrial center, the German exile Karl Marx formulated atheory on surplus-values generated from capitalist exploitation of labor. It was in the same London that he saw, and was involved in, massive labor organizing as a response to the growing misery caused by poor working condition and low wages.

In the Indies, socialism began to take root not in Batavia (the center of colonial administration), but in Surabaya, the heart and soul of industry and commerce in the early 20th century Dutch Indies.

A narrative tracing Surabaya’s development into key industrial area in the colony was penned by van Kol, a Dutch socialist who visited the city in 1903. Surabaya’s wealth, according to van Kol’s account, came from sugar plantations in smaller towns of Pasuran and Besuki, whose production shares amounted to 22.445 bouw or 22% of total sugar plantation in Java)—not to mention crops from sugar plantations in Surabaya’s hinterland region of Jombang, Kediri, and Malang.

Van Kol’s Surabaya was a vibrant industrial base with steam-run factories, cement production, coffee mills, shipyards, and warehouses housing international commodities such as coffee, sugar and oil. Aside from heavy industries, steel and chemical plants around the port helped bring about the contemporary urban environment, as well as units producing modern weapons in the colony (“Uit Onze Kolonie”. Soerabajasch Handelsblad. Van Kol, 1903).

Social life outside industrial compound also appears in Van Kol’s report. Passing through the crossroads and dark alleys around local kampongs, van Kol wrote of poverty and sex trade where Japanese, Eurasian, Chinese, and local prostitutes worked inside bamboo-walled brothels. Local medical doctors, van Kol reported, regularly checked 50 to 60 sex workers in the very places where syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases were widely spread.

Surabaya’s public hospitals (Stadsverband) were more similar to prison buildings with black bars and big padlocks than actual hospital—which explains why locals preferred traditional medical treatments to the modern one.

Other places van Kol visited were army barracks that housed war veterans, Mollucan servicemen, lower class Indos (“Eurasians”) born from concubinage—a common practice throughout the late 19th century. According to widely-held perception among Europeans in the Indies, Eurasians were considered morally downtrodden as they were brought up by local mothers who served as mistress for on-duty European officers. Needless to say, abject poverty was prevalent in this social group.

It was in such situation that Dutch socialists in the Indies built limited circles of friendship and connections. Similarity in professional background is of an interesting concern as most of them worked as engineers and teachers who occupied middle and lower class within the social structure in the colonial cities. They also supported SDAP and actively participated in the formation of the social democratic society of the Netherlands Indies.

Among Reeser’s contemporaries were Van Ravensteyn (the head of Surabaya’s HBS), Van Burink, C. Hartogh, and Bernard Cooster (Sneevliet's host in the Indies). They were part of the new social group in the colonial cities that represented the middenstand or lower middle class within the colonial bureaucracy. Like Cramer and Reeser, most of them worked as teachers and supervisors in public works centers.

Dutch socialists kept advancing their agendas notwithstanding the strict laws supressing political activities. Soon after the instigation of political reform and the founding of city council to facilitate Surabaya citizens, the Election Committe (Verkiezingscommitte) was set up in Januari 1906. The committee’s task was to ensure that voters knew who and how to vote. As van Ravensteyn and Reeser sat as chairpersons, their political influence started to manifest at least in two respects.

Firstly, the committee decided to invite women in spite of government’s decision against the right of women to elect and be elected. Surabaya’s election was thus significantly different from that of Batavia, Bandung, and Semarang in that it was the only political process that allowed to attend—though not to vote—the city’s general assembly.

Secondly, the committee decided to send invitations to 25 native Indonesians, Chinese, and other “Foreign orientals” to witness the whole electoral process. The committee also granted them the opportunity to express their opinion and aspirations in front of the European candidates (“De Kiesvergadering te Soerabaja: Mededeelingen van het Verkiezingscomite”. Soerabajasch Handelsblad. January 22, 1906).

After the founding of City Council, Reeser’s public engagement continued. In 1909, in a meeting to establish Surabaya’s Kiesvereeniging (whose duty was to prepare the city council candidates), Reeser called for the inclusion of women and natives to the association’s statute. He made no secret of his opposition to racism and patriarchy that had helped shape the attitude of most Europeans in the colony.

Reeser’s life stories demonstrate how the political issues in the colony were far larger than than what mainstream Indonesian historiography has covered so far. Race, class, nationalism, and citizenship were part and parcel of the rising urban environment in early 20th Dutch Indies.

A decade after the revoke of colonial ban on political activities, Indische Social-Demokratische Vereeniging (ISDV) was established on May 9, 1915. At the Marinegebouw, a meeting held by around thirty socialist elected Reeser the chairman of the first Social-Democratic society in the Indies. The association designated Surabaya as its headquarters. Meanwhile, Sneevliet who had just arrived in the Indies in 1912 served as the chief editor for Het Vrije Woord, the Semarang chapter of ISDV.

Since the foundation of ISDV, Dutch socialists picked up new areas to work on. This marked a new era in the colony called by Shiraishi (1990) as “the translation of modern world vocabulary” such as “social democracy”, “strike”, or“party discipline”. However, the club’s internal dynamics in itself signalled the split among socialists. The October Revolution (1917) had all the more convinced the radical faction of ISDV that a socialist revolution was not impossible in underveloped capitalist states such as Russia.

Sneevliet and his Semarang circle were in favor of a political party more independent from its mother country, in hoping that such a party could later join the Comintern. Sneevliet’s stance, however, was challenged by other members who preferred to maintain the party’s affiliation to Netherlands-based SDAP.

Defending SDAP's original position, Cramer decided to split away from ISDV and instead founded Indische Social-Democratische Partij (ISDP), a more moderate social democratic platform in the Indies.

In the middle of the political struggle, Reeser decided to return to the Netherlands only to come back to the Indies, serving as the head of HBS in Semarang. Reeser’s new occupation, coupled with new dynamics within socialist movement in the Indies he was no familiar with, contributed to his resigning from politics.

New Perspective on National Awakening

Reeser’s life stories and his politics throughout the first decade of the 20th century constitute a significant episode of modern socialism in the colony, yet an indication that the historiography of early nationalist awakening remains limited in scope and requires further revision.

Indonesian historians today face major challenges when dealing with past encounters between people, cultures and civilizations, particularly those of European background. As the Indonesia-centrist historiography was introduced in 1957 (due to a severe inferiority complex), a lot of references to the Europeans, the Dutch, and the influence of Western civilization had since been purged. As a result, the current Indonesian historiography has been increasingly isolated from global affairs.

Needless to say, it left significant impact on both political and intellectual level.

Upon his first meeting with Tjokroaminoto, Sneevliet saw him devouring De Socialisten: Personen en Stelsel. It was said that he was reading the book—a major work written by Dutch historian, legal expert, and socialist Hendrik Peter Godfried Quack—to find theoretical basis and programs for his new organization (Perthus, 1976).

It is thus clear that the Indonesian nationalist awakening did not come out of thin air. Intersections with different currents of both local and global nature are noticeable. Tjokroaminoto, being described as prominent Islamic thinker, constructed his intellectual horizon beyond Indies. He thought he had to adapt to the the global movement that had brought about the idea of class struggle to the colony. Once introduced in the Indies, the idea soon mingled with multiple expressions of race inequality, urban modernity in colonial cities, underdeveloped capitalism, and the encounter between Western modernity and Indonesian nationalism.

It takes deeper exploration than a mere reiteration of the purported "peculiarity of Indonesian history" enshrined by area studies standardized by past Western academia, from which preliminary works on Indonesian national awakening came to the fore. Two prominent examples here are Ruth T. McVey’s The Rise of Indonesian Communism, (1965) and Takashi Shiraishi’s work on popular radicalism in Java, An Age in Motion (1990).

Saying that the two major works have contributed significantly to the study of Indonesian history is an understatement. Yet a question remains: is it enough for us, researchers of Indonesian history, to uncritically depend on outdated studies?

“Each generation,” says the old adage, “writes its own history". The responsibility to further the agenda of expanding and evaluating themes and topics of the fin de siecle’s Indonesian national awakening rests with today’s Indonesian historians.

----------------------------------

Andi Achdian is a doctoral candidate in History, University of Indonesia. He serves as a managing editor for Jurnal Sejarah published by Masyarakat Sejarawan Indonesia. The original text is in Bahasa Indonesia, translated by Fitri Ratna Irmalasari,Terry Muthahhari,and Windu Jusuf.

Penulis: Andi Achdian

Editor: Windu Jusuf & Meisya Citraswara